Difference between revisions of "A Review of Maxwell's Equations & Computational Electromagnetics (CEM)"

Kazem Sabet (Talk | contribs) |

Kazem Sabet (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 196: | Line 196: | ||

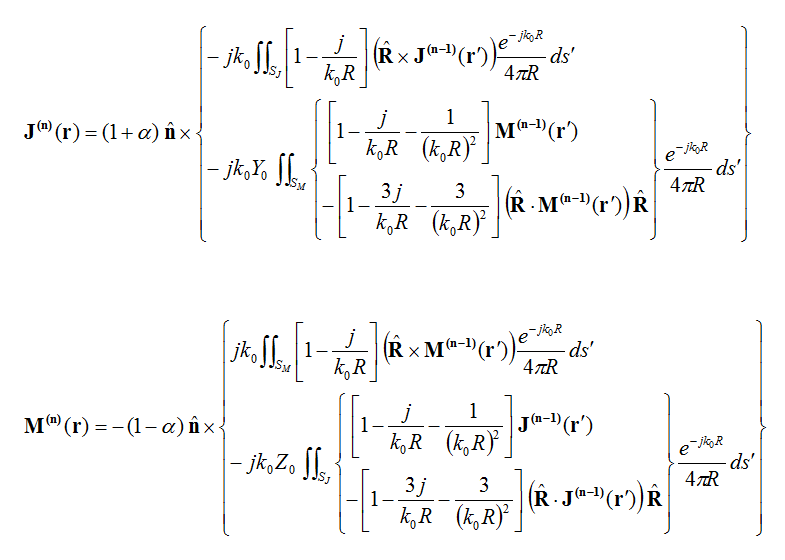

where <math> R=|r-r'| \text{, } k_0 = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda_0} \text{ and } Z_0 = 1/Y_0 = \eta_0 </math>. | where <math> R=|r-r'| \text{, } k_0 = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda_0} \text{ and } Z_0 = 1/Y_0 = \eta_0 </math>. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Differential Form of Maxwell's Equations & the Yee Cell == | == Differential Form of Maxwell's Equations & the Yee Cell == | ||

Revision as of 13:51, 8 May 2017

Contents

- 1 Maxwell's Equations in Differential Form

- 2 The Wave Equations

- 3 Electric & Magnetic Boundary Conditions

- 4 Maxwell's Equations in Integral Form

- 5 Time-Harmonic Form of Maxwell's Equations

- 6 Electric and Magnetic Potentials

- 7 Green’s Function Representations

- 8 Free-Space Field Solutions

- 9 Differential Form of Maxwell's Equations & the Yee Cell

- 10 Why Does FDTD Need Domain Termination?

- 11 CPML vs. PML

- 12 The CPML Formulation

- 13 EM.Tempo's Waveform Types

- 14 Waveform, Bandwidth, Stability

- 15 The Relationship Between Excitation Waveform and Frequency-Domain Characteristics

- 16 Normalization of Frequency-Domain Field Data

- 17 Time Domain Simulation of Periodic Structures

- 18 Free-Space Wave Propagation

- 19 Basic Wave Interaction Mechanisms

- 20 Ray Reflection & Transmission

- 21 Penetration through Thin Walls or Surfaces

- 22 Wedge Diffraction from Edges

- 23 Multilayer Green’s Functions

- 24 Planar Integral Equations

- 25 Numerical Solution of Integral Equations

- 26 Discretization Of Electric & Magnetic Currents

- 27 The Rectangular Mesh Advantage

- 28 Computing The Near Fields in Planar MoM

- 29 Computing The Far Fields in Planar MoM

- 30 Periodic Planar MoM Simulation

- 31 EM.Picasso's Linear System Solvers

- 32 Free-Space Green’s Function

- 33 3D Integral Equations

- 34 Galerkin Testing

- 35 Pocklington’s Integral Equations for Wire Structures

- 36 Discretization Of Wire Structures

- 37 Conventional Physical Optics (GO-PO)

- 38 Calculating Near & Far Fields In PO

- 39 Iterative Physical Optics (IPO)

- 40 General Huygens Sources

Maxwell's Equations in Differential Form

Maxwell's equations form the basis for the mathematical formulation of almost all electromagnetic modeling problems. The differential form of Maxwell's equations relates the electric and magnetic fields and sources locally at every point in the space. In an isotropic, time-invariant and homogeneous medium, they are given by:

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{D} = \rho [/math]

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{B} = 0 [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{E} = - \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{B}}{\partial t} [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{H} = \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{D}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{J} [/math]

where ∇ is the gradient operator:

- [math] \nabla = \dfrac{\partial}{\partial x}\hat{\mathbf{x}} + \dfrac{\partial}{\partial y}\hat{\mathbf{y}} + \dfrac{\partial}{\partial z}\hat{\mathbf{z}} [/math]

∇. denotes the divergence operation, ∇× denotes the curl operation, E and H are the electric and magnetic fields in V/m and A/m, respectively, D and B are the electric and magnetic flux densities in C/m2 and Wb, respectively, J is the electric volume current density in A/m2, ρ is the electric volume charge density in C//m3, and the following constitutive relationships hold:

- [math] \mathbf{D} = \epsilon \mathbf{E}, \quad \quad \mathbf{B} = \mu \mathbf{H}, \quad \quad \mathbf{J} = \sigma \mathbf{E} [/math]

where ε is the permittivity in F/m, μ is the permeability in H/m, and σ is the electric conductivity of the medium in S/m.

Although real magnetic charges and currents do not exist in nature, using the electromagnetic equivalence theorem, it is convenient to introduce a magnetic volume charge density in C/m3, and a magnetic volume current density M in V/m2 to preserve the symmetry and duality of Maxwell's equations in the following form:

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{D} = \rho [/math]

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{B} = \rho_m [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{E} = - \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{B}}{\partial t} - \mathbf{M} [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{H} = \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{D}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{J} [/math]

The following constitutive relationships now hold:

- [math] \mathbf{D} = \epsilon \mathbf{E}, \quad \quad \mathbf{J} = \sigma \mathbf{E} [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{B} = \mu \mathbf{H}, \quad \quad \mathbf{M} = \sigma_m \mathbf{H} [/math]

where σm is the magnetic conductivity of the medium in Ω/m.

Additionally, one can write the following continuity equations:

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{J} - \dfrac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} = 0 [/math]

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{M} - \dfrac{\partial \rho_m}{\partial t} = 0 [/math]

The Wave Equations

Combining Maxwell's equations, we can arrive at the electric and magnetic wave equations:

- [math] \nabla^2 \mathbf{E} - \epsilon \mu \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{E}}{\partial t} = 0 [/math]

- [math] \nabla^2 \mathbf{H} - \epsilon \mu \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{H}}{\partial t} = 0 [/math]

where ∇2 is the Laplacian operator. The wave equations are hyperbolic partial differential equation in space coordinates and time, which must be solved subject to the proper initial and boundary conditions.

Electric & Magnetic Boundary Conditions

The electric field boundary conditions at the interface between two material media are:

[math] \hat{\mathbf{n}} . [ \mathbf{D_2(r)} - \mathbf{D_1(r)} ] = \rho_s (\mathbf{r}) [/math]

[math] \hat{\mathbf{n}} \times [ \mathbf{E_2(r)} - \mathbf{E_1(r)} ] = - \mathbf{M_s(r)} [/math]

where [math]\hat{\mathbf{n}}[/math] is the unit normal vector at the interface pointing from medium 1 towards medium 2, and ρs is the electric surface charge density, and Ms is the magnetic surface current density at the interface.

The magnetic field boundary conditions at the interface between two material media are:

[math] \hat{\mathbf{n}} . [ \mathbf{B_2(r)} - \mathbf{B_1(r)} ] = \rho_{ms} (\mathbf{r}) [/math]

[math] \hat{\mathbf{n}} \times [ \mathbf{H_2(r)} - \mathbf{H_1(r)} ] = \mathbf{J_s(r)} [/math]

where [math]\hat{\mathbf{n}}[/math] is the unit normal vector at the interface pointing from medium 1 towards medium 2, ρms is the magnetic surface charge density, and Js is the electric surface current density at the interface.

Maxwell's Equations in Integral Form

In certain applications, it is advantageous to cast Maxwell's equations in an integral form. These can be done using the theorems of vector calculus. In an isotropic, time-invariant and homogeneous medium, the integral forms of Maxwell's equations are given by:

- [math] \int\int_S \mathbf{D} . \mathbf{ds} = \int\int\int_V \rho dv [/math]

- [math] \int\int_S \mathbf{B} . \mathbf{ds} = \int\int\int_V \rho_m dv [/math]

- [math] \int_C \mathbf{E} . \mathbf{dl} = - \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \int\int_S \mathbf{B} . \mathbf{ds} - \int\int_S \mathbf{M} . \mathbf{ds} [/math]

- [math] \int_C \mathbf{H} . \mathbf{dl} = \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t} \int\int_S \mathbf{D} . \mathbf{ds} - \int\int_S \mathbf{J} . \mathbf{ds} [/math]

where V is a closed region of the space, S the surface boundary and C is a path.

Time-Harmonic Form of Maxwell's Equations

In a time-harmonic system operating at a given frequency f, the time dependence of the fields takes the form of [math] e^{j\omega t} [/math], where [math] j = \sqrt{-1} [/math], and ω = 2πf is the angular frequency. In that case, the time derivative is [math] {\partial}/{\partial t} = j\omega [/math], and Maxwell's curl equations reduce to:

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{E} = - j\omega \mathbf{B} - \mathbf{M} [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{H} = j\omega \mathbf{D} + \mathbf{J} [/math]

and the continuity equations reduce to:

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{J} = j\omega \rho [/math]

- [math] \nabla . \mathbf{M} = j\omega \rho_m [/math]

The wave equations then reduce to the Helmholtz equations given by:

- [math] \nabla^2 \mathbf{E} + k^2 \mathbf{E} = 0 [/math]

- [math] \nabla^2 \mathbf{H} + k^2 \mathbf{H} = 0 [/math]

where [math] k = \omega \sqrt{\epsilon \mu} [/math] is the propagation constant in the medium.

Electric and Magnetic Potentials

Under the time-harmonic assumption, the electric and magnetic fields can further be expressed in terms of an electric scalar potential Φ, a magnetic scalar potential Ψ, a vector electric potential F and a vector magnetic potential A in the following form:

- [math] \mathbf{E(r)} = - \nabla \times \mathbf{F(r)} - \nabla \Phi(\mathbf{r}) - j\omega\mu \mathbf{A(r)} [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{H(r)} = \nabla \times \mathbf{A(r)} - \nabla \Psi(\mathbf{r}) - j\omega\epsilon \mathbf{F(r)} [/math]

with the additional gauge relations:

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{A(r)} = - j\omega\epsilon \Phi(\mathbf{r}) [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{F(r)} = - j\omega\mu \Psi(\mathbf{r}) [/math]

All the potential functions satisfy the Helmholtz equation:

- [math] \nabla^2 \mathbf{A} + k^2 \mathbf{A} = - \mathbf{J} [/math]

- [math] \nabla^2 \mathbf{F} + k^2 \mathbf{F} = - \mathbf{M} [/math]

- [math] \nabla^2 \Phi + k^2 \Phi = - \frac{\rho}{\epsilon} [/math]

- [math] \nabla^2 \Psi + k^2 \Psi = - \frac{\rho_m}{\mu} [/math]

Sometimes it is useful to define the Hertz vector potentials as:

- [math] \mathbf{\Pi_e} = \frac{1}{j\omega\epsilon} \mathbf{A(r)} [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{\Pi_m} = \frac{1}{j\omega\mu} \mathbf{F(r)} [/math]

In that case, the electric and magnetic fields can be fully expressed in terms of these two vector potentials:

- [math] \mathbf{E(r)} = -j\omega\mu \nabla \times \mathbf{\Pi_m} + k^2 \mathbf{\Pi_e} + \nabla \nabla . \mathbf{\Pi_e} [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{H(r)} = j\omega\epsilon\nabla \times \mathbf{\Pi_e} + k^2 \mathbf{\Pi_m} + \nabla \nabla . \mathbf{\Pi_m} [/math]

| |

For historical reasons, it is customary in electrostatic problems to directly set the magnetic flux density B equal to ∇ × A. EM.Cube's Static Module (EM.Ferma) uses that convention for definition of the vector magnetic potential A, which is different by a factor of μ from the definition of the A vector in the electrodynamic discussion presented in this section. That would also change the source term of the Helmholtz equation by the same factor. |

Green’s Function Representations

The Green’s functions are the analytical solutions of boundary value problems when they are excited by an elementary source. This is usually an infinitesimally small vectorial point source. The total electric (E) field and total magnetic (H) field can be expressed in terms of the volume electric current source J and volume magnetic current source M in the following way:

- [math] \mathbf{E = E^{inc}} + \mathbf{\iiint_{V_J} \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') \cdot J(r') } d \nu' + \mathbf{\iiint_{V_M} \overline{\overline{G}}_{EM}(r|r') \cdot M(r') } d \nu' [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{H = H^{inc}} + \mathbf{\iiint_{V_J} \overline{\overline{G}}_{HJ}(r|r') \cdot J(r') } d \nu' + \mathbf{\iiint_{V_M} \overline{\overline{G}}_{HM}(r|r') \cdot M(r') } d \nu' [/math]

where Einc and Hinc are the incident electric and magnetic fields, respectively, and VJ and VM are the volumes containing the electric and magnetic current sources, respectively. The above equations involve four dyadic Green's functions types: dyadic electric-field Green’s functions due to electric current sources GEJ, dyadic magnetic-field Green’s functions due to electric current sources GHJ, dyadic electric-field Green’s functions due to magnetic current sources GEM, and dyadic magnetic-field Green’s functions due to magnetic current sources GHM . The incident or impressed fields represent the source terms and provide the excitation of the structure.

In order for the Green’s functions to be computationally useful, they must have analytical closed forms. This can be a mathematical expression or a more complex recursive process. It is no surprise that only very few electromagnetic boundary value problems have closed-form Green’s functions. Among EM.Cube's computational modules, EM.Libera is based on the free-space Green's functions, whereas EM.Picasso is based on the dyadic Green's functions of an arbitrary multilayer planar structure.

Free-Space Field Solutions

The simplest background structure is the unbounded free space, which is represented by the following Green’s function:

- [math] \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') = (\overline{\overline{I}} + \nabla\nabla) } G_{\Lambda} (\mathbf{r|r'}), \quad G_{\Lambda} (\mathbf{r|r'}) = \frac{ e^{-jk_0 \mathbf{|r-r'|}} }{ 4\pi \mathbf{|r-r'|} } [/math]

where [math]\mathbf{\overline{\overline{I}}}[/math] is the unit dyad, [math]\nabla[/math] is the gradient operator, r and r' are the position vectors of the observation and source points, respectively, and k0 is the free-space propagation constant. This implies that electromagnetic waves propagate in free space in a spherical form away from the source. Note that the Green’s function has a singularity at the source, i.e. when r = r'.

Assuming electric and magnetic surface current sources J and M residing on surfaces SJ and SM, respectively, the near-field equations reduce to:

- [math] \begin{align} \mathbf{ E(r) = E^{inc}(r) } & - jk_0 Z_0 \iint_{S_J} \left\{ \left[ 1 - \frac{j}{k_0 R} - \frac{1}{(k_0 R)^2} \right] \mathbf{J(r')} - \left[ 1 - \frac{3j}{k_0 R} - \frac{3}{(k_0 R)^2} \right] \mathbf{ (\hat{R} \cdot J(r')) \hat{R} } \right\} \frac{e^{-jk_0 R}}{4\pi R} ds' \\ & + jk_0 \iint_{S_M} \left[ 1-\frac{j}{k_0 R} \right] \mathbf{ (\hat{R} \times M(r')) } \frac{e^{-jk_0 R}}{4\pi R} ds' \end{align} [/math]

- [math] \begin{align} \mathbf{ H(r) = H^{inc}(r) } & - jk_0 Y_0 \iint_{S_M} \left\{ \left[ 1 - \frac{j}{k_0 R} - \frac{1}{(k_0 R)^2} \right] \mathbf{M(r')} - \left[ 1 - \frac{3j}{k_0 R} - \frac{3}{(k_0 R)^2} \right] \mathbf{ (\hat{R} \cdot M(r')) \hat{R} } \right\} \frac{e^{-jk_0 R}}{4\pi R} ds' \\ & - jk_0 \iint_{S_J} \left[ 1-\frac{j}{k_0 R} \right] \mathbf{ (\hat{R} \times J(r')) } \frac{e^{-jk_0 R}}{4\pi R} ds' \end{align} [/math]

where [math] R=|r-r'| \text{, } k_0 = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda_0} \text{ and } Z_0 = 1/Y_0 = \eta_0 [/math].

Differential Form of Maxwell's Equations & the Yee Cell

Maxwell’s equations for an isotropic, time-invariant and homogeneous medium are given by:

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{E} = - \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{B}}{\partial t} - \mathbf{M} [/math]

- [math] \nabla \times \mathbf{H} = \dfrac{\partial \mathbf{D}}{\partial t} + \mathbf{J} [/math]

where E and H are the electric and magnetic fields, respectively, D and B are the electric and magnetic flux densities, respectively, J and M are the volume electric and magnetic current densities, respectively, and the following constitutive relationships hold:

- [math] \mathbf{D} = \epsilon \mathbf{E}, \quad \quad \mathbf{J} = \sigma \mathbf{E} [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{B} = \epsilon \mathbf{H}, \quad \quad \mathbf{M} = \sigma_m \mathbf{H} [/math]

where ε is the permittivity, μ is the permeability, σ is the electric conductivity, and σm is the magnetic conductivity of the medium.

In a medium without electric or magnetic losses these equations can be rewritten as:

- [math]\dfrac{\partial \mathbf{H}}{\partial t} = -\dfrac{1}{\mu} \nabla \times \mathbf{E}[/math]

- [math]\dfrac{\partial \mathbf{E}}{\partial t} = \dfrac{1}{\epsilon} \nabla \times \mathbf{H}[/math]

In the FDTD method, both time- and space-derivatives are approximated with central finite differences. This results in six differential equations, one for each field component, on a Yee cell define at a point in the 3D space as shown in the figure on the right:

- [math] H_x^{n+\frac{1}{2}} (i,j,k) = H_x^{n-\frac{1}{2}} (i,j,k) + \frac{\Delta t}{\mu (i,j,k)} \left[ \frac{E_{y}^{n}(i,j,k+1) - E_{y}^{n}(i,j,k)}{\Delta z} - \frac{E_{z}^{n} (i,j+1,k)-E_{z}^{n} (i,j,k)}{\Delta y} \right] [/math]

- [math] H_y^{n+\frac{1}{2}} (i,j,k) = H_y^{n-\frac{1}{2}} (i,j,k) + \frac{\Delta t}{\mu (i,j,k)} \left[ \frac{E_{z}^{n}(i+1,j,k) - E_{z}^{n}(i,j,k)}{\Delta x} - \frac{E_{x}^{n} (i,j,k+1)-E_{x}^{n} (i,j,k)}{\Delta z} \right] [/math]

- [math] H_z^{n+\frac{1}{2}} (i,j,k) = H_z^{n-\frac{1}{2}} (i,j,k) + \frac{\Delta t}{\mu (i,j,k)} \left[ \frac{E_{x}^{n}(i,j+1,k) - E_{x}^{n}(i,j,k)}{\Delta y} - \frac{E_{y}^{n} (i+1,j,k)-E_{y}^{n} (i,j,k)}{\Delta x} \right] [/math]

- [math] {E_{x}^{n+1} (i,j,k) = E_{x}^{n} (i,j,k)} + \frac{\Delta t}{\epsilon (i,j,k)} \left[ \frac{H_{z}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k) - H_{z}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j-1,k)}{\Delta y} - \frac{H_{y}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k) - H_{y}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k-1)}{\Delta z} \right] [/math]

- [math] {E_{y}^{n+1} (i,j,k) = E_{y}^{n} (i,j,k)} + \frac{\Delta t}{\epsilon (i,j,k)} \left[ \frac{H_{x}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k) - H_{x}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k-1)}{\Delta z} - \frac{H_{z}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k) - H_{z}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i-1,j,k)}{\Delta x} \right] [/math]

- [math] {E_{z}^{n+1} (i,j,k) = E_{z}^{n} (i,j,k)} + \frac{\Delta t}{\epsilon (i,j,k)} \left[ \frac{H_{y}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k) - H_{y}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i-1,j,k)}{\Delta x} - \frac{H_{x}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j,k) - H_{x}^{n+\frac{1}{2} } (i,j-1,k)}{\Delta y} \right] [/math]

where i, j, k are the grid position indices along the X, Y, Z axes, respectively, n is the current time step index and Δx, Δy, Δz are the grid position indices along the X, Y, Z axes, respectively. Similar expressions are obtained for the Y and Z components of the electric and magnetic fields. When your physical structure involves lossy materials with nonzero electric conductivity σ and/or nonzero electric conductivity σm, the above update equations become more complicated. In the case of anisotropic materials with tensorial constitutive parameters, the electric displacement vector D and magnetic induction vector B need to be involved in the update of Maxwell's equations at every time step. This results in a total of twelve update equations at every time step. In the case of dispersive materials with time-varying constitutive parameters, additional auxiliary differential equations are invoked and updated at every time step. Applying the proper boundary conditions for all the materials inside the computational domain and at the boundaries of the domain itself, EM.Cube calculates and "updates" all the necessary field components at every mesh node, at every time step.

Why Does FDTD Need Domain Termination?

The FDTD simulation time depends directly on the size of the computational domain. For free space radiation or scattering problems, the computational domain must be extended to infinity, which means an infinite number of cells in the computational domain. The solution to this problem is to truncate the domain by a set of artificial boundaries at a certain distance from the objects in the computational domain. The absorbing boundaries should be such that the field propagates through them without any back reflection. Different methods have been used to simulate an absorbing boundary condition in FDTD simulations. The most common ones are Mur, Liao, and the perfectly match layer (PML). The Mur boundary condition calculates the boundary field values from the three dimensional scalar wave equations, while the Liao boundary condition is based on extrapolation of the fields in space and time. In 1994, Berenger proposed a new boundary condition called the perfectly matched layer (PML), which provides a much better performance than the Liao and Mur boundary conditions. The PML medium properties surrounding the computational domain are chosen to effectively absorb all the outgoing waves propagating towards the boundaries. In PML regions, an artificial conductivity is introduced such that it starts with very small values at the free space-PML interfaces and gradually increases until it reaches its maximum value at the last layer of the PML region.

CPML vs. PML

The PML boundary condition is not effective in absorbing evanescent waves, and it suffers from late-time reflections when simulating fields with very long time signatures. This is partly due to the weakly causal nature of the PML. A strictly causal form of the PML, known as the complex frequency-shifted PML (CFS-PML), was later developed by simply shifting the frequency dependent pole off the real axis and into the negative-imaginary half of the complex plane. It has been shown that the CFS-PML is highly effective at absorbing evanescent waves and signals with a long time signature. Therefore, using the CFS-PML, the boundaries can be placed closer to the objects in the computational domain, and considerable time and memory savings can be achieved. The convolutional PML (CPML) is an efficient implementation of the CFS-PML based on a stretched coordinate formulation in conjunction with recursive convolution. It has been shown that CPML requires only two auxiliary variables per discrete field point and absorbs waves in isotropic, homogeneous, inhomogeneous, lossy, dispersive, anisotropic or non-linear media without any further generalization.

The CPML Formulation

The CPML is formulated in the stretched coordinate space. The CPML layers are assumed to terminate the FDTD computational domain. The X components of Maxwell's frequency-domain curl equations can then be written in the following form:

- [math] (j\omega\epsilon_x + \sigma_{ex})\tilde{E}_x = \frac{1}{s_{ey}} \frac{\partial \tilde{H}_z}{\partial y} - \frac{1}{s_{ez}} \frac{\partial \tilde{H}_y}{\partial z} [/math]

- [math] (j\omega\mu_x + \sigma_{mx}) \tilde{H}_x = -\frac{1}{s_{my}} \frac{\partial \tilde{E}_z}{\partial y} + \frac{1}{s_{mz}} \frac{\partial \tilde{E}_y}{\partial z} [/math]

where sei and smi are the stretched coordinate metrics defined by:

- [math] s_{ei} = \kappa_{ei} + \frac{\sigma_{ei}}{\alpha_{ei} + j\omega\varepsilon_0}, \quad i=x,y,z [/math]

- [math] s_{mi} = \kappa_{mi} + \frac{\sigma_{mi}}{\alpha_{mi} + j\omega\mu_0}, \quad i=x,y,z [/math]

sei and smi are the anisotropic components of the synthesized electric and magnetic conductivities in the CPML region. κei , κmi, αei and αmi are all assumed to be positive real and κei, κmi ≥ 1. Similar equations hold for the Y and Z components of the electric and magnetic fields in the CPML layers. The requirement for zero reflection at PML-PML interfaces imposes the following condition:

- [math] s_{ei} = s_{mi} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \kappa_{ei} = \kappa_{mi} ,\quad \frac{\sigma_{ei}}{\varepsilon_0} = \frac{\sigma _{mi}}{\mu_0}, \quad \frac{\alpha_{ei}}{\varepsilon_0} = \frac{\alpha_{mi}}{\mu _0} [/math]

The tilde notation above denotes the Fourier transform of the field components in the frequency domain. Transforming the above equations back to the time domain, one encounters convolution on the right hand side due to the frequency dependence of the stretched coordinate metrics:

- [math] \left(\varepsilon_x \frac{\partial E_x}{\partial t} + \sigma_{ex}E_x \right) = \breve{s}_{ey}(t) \frac{\partial H_z}{\partial y} - \breve{s}_{ez}(t)\frac{\partial H_y}{\partial z} [/math]

- [math] \left(\mu_x \frac{\partial H_x}{\partial t} + \sigma_{mx}H_x \right) = -\breve{s}_{my}(t)\frac{\partial E_z}{\partial y} + \breve{s}_{mz}(t)\frac{\partial E_y}{\partial z} [/math]

where šei(t) and šmi(t) denote functions of time that are indeed the inverse Laplace transform of sei-1 and smi-1,respectively, given by:

- [math] \breve{s}_{ei}(t) = \frac{\delta(t)}{\kappa_{ei}} - \frac{\sigma_{ei}}{\kappa_{ei}^2} u(t)\exp \left[-\left(\frac{\sigma_{ei}}{\kappa_{ei}} + \alpha_{ei} \right)\frac{t}{\varepsilon_0} \right] [/math]

- [math] \breve{s}_{mi}(t) = \frac{\delta(t)}{\kappa_{mi}} - \frac{\sigma_{mi}}{\kappa_{mi}^2} u(t)\exp \left[-\left(\frac{\sigma_{mi}}{\kappa_{mi}} + \alpha_{mi} \right)\frac{t}{\mu_0} \right] [/math]

where d(t) and u(t) denote the Dirac delta and unit step functions, respectively. The convolutions on the right hand side of the time domain equations can be accelerated by the use of the recursive convolution (RC) method.

The CPML parameters are chosen to be an increasing function of the distance from the boundaries of the computational domain. EM.Cube uses a polynomial profile of degree nPML. Given the interrelationships among these parameters, one can write:

- [math] \sigma_{ei}(r) = \frac{\varepsilon_0}{\mu_0}\sigma_{mi}(r) = \sigma_{max}\left( \dfrac{r}{\delta} \right)^{n_{PML}} [/math]

- [math] \kappa_{ei}(r) = \kappa_{mi}(r) = 1 + \left( \kappa_{max} - 1 \right) \left( \dfrac{r}{\delta} \right)^{n_{PML} } [/math]

- [math] \alpha_{ei}(r) = \frac{\varepsilon_0}{\mu_0} \alpha_{mi}(r) = \alpha _{min} + \left(\alpha_{max } - \alpha_{min } \right) \left( \frac{r}{\delta} \right)^{n_{PML}} [/math]

where r is the distance of field observation point inside the CPML layer from the edge of the computational domain. The parameters σmax, κmax, αmin and αmax as well as nPML can be modified by the user.

EM.Tempo's Waveform Types

The accuracy of the FDTD simulation results depends on the right choice of temporal waveform. The excitation waveform is the temporal source function that sets the initial conditions at t = 0 and provides an excitation signal afterwards. EM.Tempo currently offers four different choices:

- Sinusoidal

- Gaussian Pulse

- Modulated Gaussian Pulse

- Custom

EM.Tempo's default waveform choice is a modulated Gaussian pulse. If you use a Gaussian pulse or a modulated Gaussian pulse waveform to drive your FDTD source, after a certain number of time steps, the total energy of the computational domain drops to very negligible levels. At that point, you can consider your solution to have converged. If you drive your FDTD source by a sinusoidal waveform, the total energy of the computational domain will oscillate indefinitely, and you have to force the time loop to terminate after a certain number of time steps assuming a steady state have been reached.

Waveform, Bandwidth, Stability

The FDTD method provides a wideband simulation of your physical structure. Frequency domain techniques often require a tedious frequency sweep to calculate the port characteristics (S/Y/Z parameters). By contrast, EM.Tempo performs a discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of the time domain data to calculate these characteristics at the end of a single FDTD simulation run. In order to produce sufficient spectral information, an appropriate wideband temporal waveform is needed to excite the physical structure. The general form of EM.Tempo's default excitation waveform is a Modulated Gaussian Pulse given by:

- [math] E_j^{inc}(r,t)=E_0(r) \exp \left(-\frac{(t-t_0)^2}{\tau ^2} \right) \cos \left(2\pi f_0 (t-t_0)-\Phi \right),\quad j=x,y,z [/math]

where f0 is the center frequency, t0 is the time delay, t is the Gaussian pulse width, and Φ is a constant phase. In the limits, the above waveform can be reduced either to a simple Gaussian pulse:

- [math] E_j^{inc}(r,t) = E_0(r) \exp \left(-\frac{(t-t_0)^2}{\tau ^2} \right),\quad j=x,y,z [/math]

or to a continuous, single-tone, sinusoidal waveform with a frequency of f0:

- [math] E_j^{inc}(r,t) = E_{0} (r)\cos (2\pi f_0 (t-t_0)-\Phi),\quad j=x,y,z [/math]

The choice of the waveform, its bandwidth and time delay are important for the convergence behavior of the FDTD time marching loop. By default, EM.Tempo uses a modulated Gaussian waveform with optimal parameters: t = 0.966/Δf and t0 = 4.5t, where Δf is the specified bandwidth of the simulation. The time delay t0 is chosen so that the temporal waveform has an almost zero value at t = 0. Of the above waveforms, modulated Gaussian and sinusoidal waveforms are band pass with no DC content, while the Gaussian pulse is low pass with a frequency spectrum that is concentrated around f = 0. In a typical FDTD simulation, you set a center frequency for the structure of interest and then specify a bandwidth around this center frequency. These together determine the lowest and highest spectral contents of your FDTD waveform. Note that setting a bandwidth equal to 2f0 sets the lowest frequency to DC (fmin = 0), which you may want to avoid in certain applications. On the other hand, using a Gaussian pulse waveform, you do want to set Δf = 2f0. In contrast to the wideband, exponentially decaying, Gaussian pulse and modulated Gaussian waveforms, the sinusoidal waveform is extremely narrowband and single-frequency indeed. It does not decay over time and continues to oscillate indefinitely after reaching a steady state.

Another issue of concern in an FDTD simulation is the numerical stability of the time marching scheme. You can set the mesh grid cell size to any fraction of a wavelength. Normally, you would expect to get better and more accurate results if you increase the mesh resolution. However, the time step is inversely proportional to the maximum grid cell size in order to satisfy the Courant-Friedrichs-Levy (CFL) stability condition:

- [math] \Delta t \le \frac{K_{CFL}} {c\sqrt{\left(\dfrac{1}{\Delta x_{min}} \right)^2 + \left(\dfrac{1}{\Delta y_{min}} \right)^2 + \left(\dfrac{1}{\Delta z_{min}} \right)^2 } } [/math]

where c is the speed of light, and KCFL is a constant. EM.Tempo uses a default value of KCFL = 0.9. For a uniform grid with equal cell dimensions along the X, Y and Z directions, i.e. Δx = Δy = Δz = Δ, and the CFL condition reduces to:

- [math] \Delta t \le K_{CFL} \frac{\Delta}{\sqrt{3}c}[/math]

As can be seen from the above criterion, a high resolution mesh requires a smaller time step. Since you need to let the fields in the computational domain fully evolve over time, a smaller time step will require a larger number of time steps to achieve convergence. EM.Tempo automatically chooses a time step that satisfies the CFL condition.

The Relationship Between Excitation Waveform and Frequency-Domain Characteristics

The accuracy of the FDTD simulation results depends on the right choice of temporal waveform. At the end of an FDTD simulation, the time domain field data are transformed into the frequency domain at your specified frequency or bandwidth to produce the desired observables. The frequency at which the frequency-domain characteristics are computed is usually the same as the center frequency of your project, but it doesn't have to be as long as it falls within the project's bandwidth. Different waveforms have different spectral behaviors. It is critical that you understand the time-domain-to-frequency-domain transformations in order to correctly interpret some simulation data.

If you open up the property dialog of any source type in EM.Tempo, you will see an Excitation Waveform... button located in the "Source Properties" section of the dialog. Clicking this button opens up EM.Tempo's Excitation Waveform dialog. From this dialog, you can override EM.Tempo's default waveform and customize your own temporal waveform.

The sinusoidal waveform has a frequency f0 equal to the project's center frequency and does not have any parameter that you can modify. The delay in this case is set to t0 = 1/(4f0) so that the waveform vanishes at t = 0:

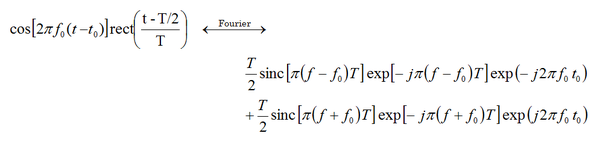

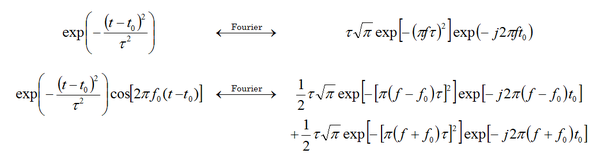

where sinc(x) = sin(πx) / (πx), and T is the length of the temporal window from t = 0 to the exit time t = NΔt, and Δt is the time step of the time marching loop.

For Gaussian and modulated Gaussian waveforms you can set the pulse width and time delay. The pulse width should be chosen such that the Fourier transform of your selected waveform encompasses your project bandwidth. Rather than setting an arbitrary pulse width, EM.Cube lets you set a parameter called Spectral Truncation Level or delta (δ), which is the normalized truncation threshold for the spectral content of the excitation pulse. This is explained as follows. Recall that the Fourier transform of a Gaussian pulse is also a Gaussian pulse. The Fourier transform of a modulated Gaussian pulse consists of two Gaussian pulses located at the two opposite sides of f = 0 (DC) shifted by the modulation frequency f0:

Since a Gaussian pulse waveform has considerable DC content, it must be used to model lowpass structures. In that case, the center frequency and bandwidth of the project must be set such that Δf = 2f0 and hence, fmin = f0 - Δf/2 = 0, and fmax = f0 + Δf/2 = 2f0. The width τ of the temporal Gaussian pulse is then determined such that at fmax the spectral Gaussian pulse drops to the δ-level from its maximum value of 1. With a bandwidth of Δf, the pulse width must satisfy the following equation:

- [math] \exp[-(\pi f_{\delta} \tau)^2] = \exp[-(\pi \Delta f \tau)^2] = \delta \quad \Rightarrow \quad \tau = \frac{\sqrt{-\ln\delta}}{\pi f_{max}} [/math]

When you set δ = 0.1 (the default value), it means that the Fourier transform of your excitation waveform drops to 10% of its peak at the upper edge of your specified frequency range. For a Modulated Gaussian pulse waveform with a bandwidth of Δf, the pulse width must satisfy the following equation:

- [math] \exp[ -[\pi(f_{\delta} - f_0)\tau] ^2 ] = \exp \left[ -\left(\pi \frac{\Delta f}{2} \tau\right)^2 \right] = \delta \quad \Rightarrow \quad \tau = \frac{2\sqrt{-\ln \delta}}{\pi \Delta f} [/math]

For the default value of δ = 0.1, you get the standard relation: τ = 0.966 / BW, which is typically used for modulated Gaussian waveforms. The source waveform requires a time delay t0 so that its value drops to almost zero at t = 0. The time delay is expressed in terms of a multiple of the pulse width: t0 / tau, and its default value is 4.5.

Keep in mind that FDTD is a time domain algorithm. At the end of an FDTD simulation, a Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) is performed on the time domain data to calculate frequency domain characteristics such as near fields, far field radiation patterns, RCS, S/Y/Z parameters, etc.:

- [math]\tilde{F}(f) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(t) e^{-j2\pi f t} \, dt \quad \approx \quad \Delta t \sum_{n=0}^N f(n\Delta t) e^{-j2 \pi n f \Delta t} [/math]

Of EM.Tempo's observables, the near fields, far fields and all of their associated parameters like directivity, RCS, etc., are calculated at a certain frequency that is specified as part of the definition of the observable. On the other hand, port characteristics like S/Y/Z parameters, VSWR and periodic characteristics like reflection and transmission coefficients, are calculated over the entire specified bandwidth of your project. In other words, you get a wideband frequency response at the end of a single time domain FDTD simulation run. The number of frequency point data over this bandwidth is equal to the number of DFT samples that are generated during the time marching loop. This number is set to 200 by default. In other words, 200 frequency data are generated at the end of an FDTD simulation. You can change this number through the box labeled No. DFT Samples in the "Discrete Fourier Transform" section of the FDTD Simulation Engine Settings dialog.

Normalization of Frequency-Domain Field Data

From the above equations, it can be seen that the discrete Fourier transform multiplies the samples of time-domain field quantities by the time step Δt. This means that the resulting Fourier transforms of electric and magnetic field components now have units of V/m/Hz or A/m/Hz, respectively. Moreover, the Fourier transforms of the three waveform types have different spectral values at the observation frequency f0. This makes it difficult to compare the FDTD simulation results with the results from EM.Cube's other computational modules. For example, in the Planar, MoM3D and Physical Optics Modules, a plane wave source typically has a complex-valued functional form of exp(-jk0k.r), which has a unit magnitude. In EM.Tempo, the time domain plane wave source has a functional dependence of the following form:

- [math] \mathbf{E^{inc}}(r,t) = (E_{\theta}^{inc} \hat{\theta} + E_{\phi}^{inc} \hat{\phi}) f \left[ (t-t_0) - \frac{\mathbf{\hat{k} \cdot r} - l_0}{c} \right] [/math]

where f(t) is the temporal waveform, t0 is the time delay, l0 is a spatial shift, and c is the speed of light in the free space. The Fourier transform of the above temporal function evaluated at f = f0 has an amplitude different than 1. For this purpose, EM.Tempo normalizes the temporal waveform by the magnitude of its Fourier transform at the observation frequency f0. As a result, a temporal plane source with any of the three waveform types will always create spectral incident source with |Einc(r, f0)| = 1. The temporal waveform normalization factors for the three waveform types are given below:

- [math] \begin{align} &(N.F.)_{Sinusoidal} = \frac{2}{T} = \frac{2}{N \Delta t} \\ &(N.F.)_{Gaussian} = \frac{ e^{(\pi f_0 \tau)^2} }{ \sqrt{\pi} \tau } = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi} \tau \delta^{1/4}} \\ &(N.F.)_{Modulated} = \frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi} \tau} \end{align} [/math]

Time Domain Simulation of Periodic Structures

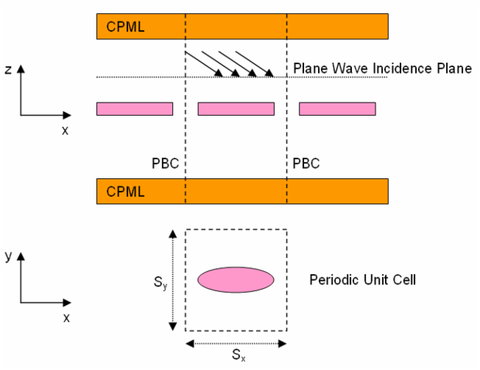

A periodic structure is one that repeats itself infinitely in one, two or three directions. EM.Tempo allows you to simulate doubly periodic structures with periodicities along the X and Y directions. Many interesting structures such as frequency selective surfaces (FSS), electromagnetic band-gap (EBG) structures and metamaterial structures can be modeled using periodic geometries. In the case of an infinitely extended periodic structure, it is sufficient to analyze only a unit cell. In the FDTD method, this is accomplished by applying periodic boundary conditions (PBC) at the side walls of the computational domain. The application of the PBC is straightforward for the case of a normally incident plane wave source since the fields do not experience any delay as they travel across the unit cell. Obliquely incident plane waves, on the other hand, cause a time delay in the transverse plane. This delay requires knowledge of the future values of the fields at any time step.

A number of techniques have been proposed to solve this problem. EM.Cube uses a recently developed novel technique that is known as Direct Spectral FDTD or Constant Transverse Wavenumber method. In this technique, the components of the transverse (horizontal) wavenumber are kept constant in the direction of periodicity. This technique shows a significant advantage over the other methods for simulation of the incident illuminations close to the grazing angles.

The figure above shows a doubly periodic structure with periods Sx and Sy along the X and Y directions, respectively. The computational domain is terminated with PBC in both X and Y directions. Along the positive and negative Z directions, it is terminated with CPML layers. Bear in mind that the PBC is also applied to the CPML layers. The computational domain is excited by a TMz or TEz plane wave incident at z = z0. The plane wave incidence angles are denoted by θ (elevation) and φ (azimuth) in the spherical coordinate system. The constant wavenumber components kx and ky in this case are defined as:

- [math]k_x = k_0 \sin\theta\cos\phi[/math]

- [math]k_y = k_0 \sin\theta \sin\phi[/math]

where [math]k_0 = \omega/c = 2\pi f/c = 2\pi/\lambda_0[/math] is the free space propagation constant, f is the operational frequency, ω is the angular frequency, λ0 is the free space wavelength, c is the speed of light in the free space. The constant transverse wavenumber kl is then given by:

- [math] k_l = \sqrt{k_x^2 + k_y^2} = k_0\sin\theta [/math]

which depends only on θ and not on φ. On the excitation plane, the incident field adopts a modulated Gaussian waveform and a complex phase delay along the periodicity direction with the following form:

- [math] H_x^{inc}(x,y,t) = -\frac{1}{\eta_0} \sin\phi \; \exp \left(-\frac{(t-t_0)^2}{\tau^2} \right) \exp(j2\pi f_0 t) \exp(-jk_x x) \exp(-jk_y y)[/math]

- [math] H_y^{inc}(x,y,t) = \frac{1}{\eta_0} \cos\phi \; \exp \left(-\frac{(t-t_0)^2}{\tau^2} \right) \exp(j2\pi f_0 t) \exp(-jk_x x) \exp(-jk_y y)[/math]

for TMz polarization and

- [math] E_x^{inc}(x,y,t) = \sin\phi \; \exp \left(-\frac{(t-t_0)^2}{\tau^2} \right) \exp(j2\pi f_0 t) \exp(-jk_x x) \exp(-jk_y y)[/math]

- [math] E_y^{inc}(x,y,t) = -\cos\phi \; \exp \left(-\frac{(t-t_0)^2}{\tau^2} \right) \exp(j2\pi f_0 t) \exp(-jk_x x) \exp(-jk_y y)[/math]

for TEz polarization. Here, f0 is the center frequency of the modulated Gaussian pulse waveform, t0 is the time delay, and τ is the Gaussian pulse width. The choices of the Gaussian waveform parameters are very critical in order to avoid possible resonances. For a fixed value of kl, the horizontal resonance occurs at:

- [math] f_{res} = \frac{k_l c}{2 \pi} [/math]

For a fixed frequency [math]f_0[/math] and a fixed incidence angle [math]\theta_0[/math], the resonant frequency is reduced to:

- [math] f_{res} = f_0 \mathbf{\sin} \theta_0 [/math]

The modulated Gaussian waveform must be chosen such that its effective bandwidth avoids the horizontal resonant frequency. Otherwise, the temporal response of the structure starts to oscillate, and the time marching loop will not converge. To avoid this problem, the modulation frequency and bandwidth of the waveform are chosen to satisfy the following condition:

- [math] f_{mod} \ge f_{res} + \dfrac{1}{2}\Delta f = \dfrac{k_{l,fixed}\;c}{2\pi} + \dfrac{1}{2}\Delta f [/math]

Free-Space Wave Propagation

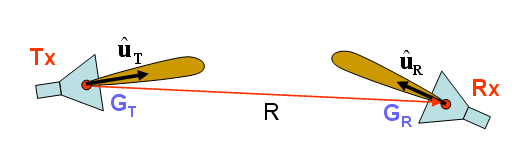

In a free-space line-of-sight (LOS) communication system, the signal propagates directly from the transmitter to the receiver without encountering any obstacles (scatterers). Electromagnetic waves propagate in the form of spherical waves with a functional dependence of ej(ωt-k0R)/R, where R is the distance between the transmitter and receiver, [math]\omega = 2\pi f[/math], f is the signal frequency, [math]k_0 = \frac{\omega}{c} = \frac{2\pi}{\lambda}[/math], c is the speed of light, and λ0 is the free-space wavelength at the operational frequency. By the time the signal arrives at the location of the receiver, it undergoes two changes. It is attenuated and its power drops by a factor of 1/R2, and additionally, it experiences a phase shift of [math]\frac{2\pi R}{\lambda_0}[/math], which is equivalent to a time delay of R/c. The signal attenuation from the transmitter to the receiver is usually quantified by Path Loss defined as the ratio of the received signal power (PR) to the transmitted signal power (PT). Assuming isotropic transmitting and receiving radiators (i.e. radiating uniformly in all directions), the Path Loss in a free-space line-of-sight communication system is given by Friis’ formula:

- [math] \frac{P_R}{P_T} = \left( \frac{\lambda_0}{4\pi R} \right)^2 [/math]

The above formula assumes that the receiving antenna is polarization-matched. Normally, there is a polarization mismatch between the transmitting and receiving antennas. In the case of directional transmitting and receiving antennas, Friis’ formula takes the following form:

- [math] P_R = P_T \, G_T G_R \left( \frac{\lambda_0}{4\pi R} \right)^2 \left| \mathbf{ \hat{u}_T \cdot \hat{u}_R } \right|^2 [/math]

where uT and uR are the unit polarization vectors of the transmitting and receiving antennas, and GT and GR are their gains, respectively.

Basic Wave Interaction Mechanisms

EM.Terrano discretizes all of the objects in your propagation scene into flat triangular facets. Obviously, rectangular and cubic objects preserve their geometric shapes through this discretization. Objects with curved surfaces such as cylinders, cones or spheres, are approximated by triangular surface mesh representations. The geometric fidelity of the resulting mesh depends on the specified mesh edge length. When a ray hits a triangular facet, the propagating spherical wave is approximated as a plane wave at the specular point. The reflection and transmission coefficients of the surface are calculated at the operational frequency and at the particular ray incident angle.

A new reflected ray is generated at the specular point, which starts traveling and bouncing around in the scene. If the obstructing surface is penetrable, a second transmitted ray is generated and added to the scene. If the ray hits the edge of an obstacle, it is diffracted from that edge. This leads to the creation of a cone of new rays, which greatly complicate the computational problem. The Uniform Theory of Diffraction (UTD) is used to calculate the wedge diffraction coefficients at the edges of scattering blocks. Note that reflection, transmission and diffraction coefficients are all dependent on the polarization of the incident plane wave.

A receiver may receive a large number of rays: direct line-of-sight rays from the transmitter, rays reflected or diffracted off the ground or terrain, rays reflected or diffracted from buildings or rays transmitted through buildings. Each received ray is characterized by its power, delay and angles of arrival, which are the spherical coordinate angles θ and φ of the incoming ray. The actual signal received and detected by the receiver is the superposition of all these rays with different power levels and different time delays. Most of the time, you will be interested in the coverage map of an area, which shows how much power is received by a grid of receivers spread over the area from a given fixed transmitter.

Ray Reflection & Transmission

The incident, reflected and transmitted rays are each characterized by a triplet of unit vectors:

- [math]( \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\|}, \hat{u}_{\perp}, \hat{k} } )[/math] representing the incident parallel polarization vector, incident perpendicular polarization vector and incident propagation vector, respectively.

- [math]( \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\|}^{\prime}, \hat{u}_{\perp}', \hat{k}' } )[/math] representing the reflected parallel polarization vector, reflected perpendicular polarization vector and reflected propagation vector, respectively.

- [math]( \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\|}^{\prime\prime}, \hat{u}_{\perp}^{\prime\prime}, \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} } )[/math] representing the transmitted parallel polarization vector, transmitted perpendicular polarization vector and transmitted propagation vector, respectively.

The reflected ray is assumed to originate from a virtual image source point. The three triplets constitute three orthonormal basis systems. Below, it is assumed that the two dielectric media have permittivities ε1 and ε2, and permeabilities μ1 and μ2, respectively. A lossy medium with a conductivity σ can be modeled by a complex permittivity εr = ε'r –jσ/ε0. Assuming n to be the unit normal to the interface plane between the two media, and Z0 = 120Ω , the incident polarization vectors as well as all the reflected and transmitted vectors are found as:

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\perp} = \frac{\hat{k} \times \hat{n}}{|\hat{k} \times \hat{n}|} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\|} = \hat{u}_{\perp} \times \hat{k} } [/math]

The reflected unit vectors are found as:

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{k}' = \hat{k} - 2(\hat{k} \cdot \hat{n}) \hat{n} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\perp}' = \hat{u}_{\perp} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\|}' = \hat{u}_{\perp}' \times \hat{k}' } [/math]

The transmitted unit vectors are found as:

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} = \hat{n} \times a - \sqrt{1-a \cdot a} \; \hat{n} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\perp}^{\prime\prime} = \hat{u}_{\perp} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_{\|}^{\prime\prime} = \hat{u}_{\perp}^{\prime\prime} \times \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} } [/math]

where

- [math] \mathbf{a} = (k_1/k_2) \mathbf{\hat{k} \times \hat{n}}[/math]

- [math] k_1 = k_0 \sqrt{\varepsilon_1 \mu_1} [/math]

- [math] k_2 = k_0 \sqrt{\varepsilon_2 \mu_2} [/math]

- [math] \eta_1 = Z_0 \sqrt{\mu_1 / \varepsilon_1} [/math]

- [math] \eta_2 = Z_0 \sqrt{\mu_2 / \varepsilon_2} [/math]

- [math] \sin\theta^{\prime\prime} = \frac{k_1}{k_2}\sin\theta \text{ if } \sin\theta \le k_2/k_1[/math]

The reflection coefficients at the interface are calculated for the two parallel and perpendicular polarizations as:

- [math] R_{\|} = \frac { \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) - \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) } { \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) + \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) } = \frac{\eta_2 \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} - \eta_1 \cos\theta} {\eta_2 \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} + \eta_1 \cos\theta} = \frac{Z_{2\|} - Z_{1\|}} {Z_{2\|} + Z_{1\|}} [/math]

- [math] R_{\perp} = \frac { \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) - \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) } { \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) + \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) } = \frac{\eta_2 / \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} - \eta_1 / \cos\theta} {\eta_2 / \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} + \eta_1 / \cos\theta} = \frac{Z_{2\perp} - Z_{1\perp}} {Z_{2\perp} + Z_{1\perp}} [/math]

Penetration through Thin Walls or Surfaces

In "Thin Wall Approximation", we assume that an incident ray gives rise to two rays, one is reflected at the specular point, and the other is transmitted almost in the same direction as the incident ray. The reflected ray is assumed to originate from a virtual image source point. Similar to the case of reflection and transmission at the interface between two dielectric media, here too we have three triplets of unit vectors, which all form orthonormal basis systems.

The transmission coefficients are calculated for the two parallel and perpendicular polarizations as:

- [math] T_{\|} = \frac{(1-{\Gamma_{\|}}^2) \exp(-jk_2 d (\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n}}))} { 1-{\Gamma_{\|}}^2 \exp( -2jk_2 d (\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) ) } [/math]

- [math] T_{\perp} = \frac{(1-{\Gamma_{\perp}}^2) \exp(-jk_2 d (\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n}}))} { 1-{\Gamma_{\perp}}^2 \exp( -2jk_2 d (\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) ) } [/math]

where

- [math] \Gamma_{\|} = \frac{ \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) - \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) } { \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) + \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) } = \frac{\eta_2 \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} - \eta_1 \cos\theta} {\eta_2 \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} + \eta_1 \cos\theta} = \frac{Z_{2\|} - Z_{1\|}} {Z_{2\|} + Z_{1\|}} [/math]

- [math] \Gamma_{\perp} = \frac{ \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) - \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) } { \eta_2(\mathbf{ \hat{k} \cdot \hat{n} }) + \eta_1(\mathbf{ \hat{k}^{\prime\prime} \cdot \hat{n} }) } = \frac{\eta_2 / \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} - \eta_1 / \cos\theta} {\eta_2 / \cos\theta^{\prime\prime} + \eta_1 / \cos\theta} = \frac{Z_{2\perp} - Z_{1\perp}} {Z_{2\perp} + Z_{1\perp}} [/math]

Wedge Diffraction from Edges

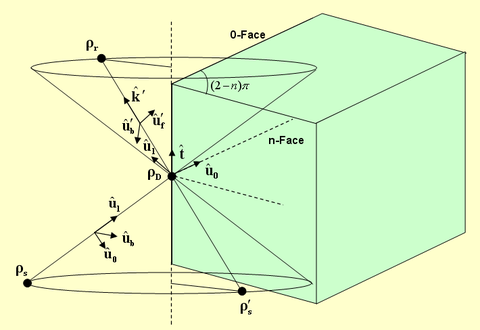

For the purpose of calculation of diffraction from building edges, we define a "Wedge" as having two faces, the 0-face and the n-face. The wedge angle is a = (2-n)p, where the parameter n is required for the calculation of diffraction coefficients. All the diffracted rays lie on a cone with its vertex at the diffraction point and a wedge angle equal to the angle of incidence in the opposite direction. A diffracted ray is assumed to originate from a virtual image source point. Three triplets of unit vectors are defined as follows:

- [math]\mathbf{(\hat{u}_0, \hat{u}_l, \hat{t})}[/math] representing the unit vector normal to the edge and lying in the plane of the 0-face, the unit vector normal to the 0-face, and the unit vector along the edge, respectively.

- [math]\mathbf{(\hat{u}_f, \hat{u}_b, \hat{t})}[/math] representing the incident forward polarization vector, incident backward polarization vector and incident propagation vector, respectively.

- [math]\mathbf{(\hat{u}_f', \hat{u}_b', \hat{t}')}[/math] representing the diffracted forward polarization vector, diffracted backward polarization vector and diffracted propagation vector, respectively.

The three triplets constitute three orthonormal basis systems. The propagation vector k' of the diffracted ray has to be constructed based on the diffraction cone as follows:

- [math] \mathbf{\hat{k}'} = \cos\phi_w \mathbf{\hat{u}_0} + \sin\phi_w \mathbf{\hat{u}_l} + \mathbf{(\hat{k} \cdot \hat{t}) \hat{t}}, \quad 0 \le \phi_w \le \alpha[/math]

where the resolution of the angle θw is chosen to be the same as the resolution of the incident ray.

The other unit vectors for the incident and diffracted rays are found as:

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_f = \frac{\hat{k} \times \hat{t}}{|\hat{k} \times \hat{t}|} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_b = \hat{k} \times \hat{u}_f } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_f' = \frac{\hat{k}' \times \hat{t}}{|\hat{k}' \times \hat{t}|} } [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{ \hat{u}_b' = \hat{k}' \times \hat{u}_f' } [/math]

The diffraction coefficients are calculated in the following way:

- [math] D_s = \frac{-e^{-j\pi/4}}{2n \sqrt{2\pi k} \sin\beta_0'} \left\lbrace \begin{align} & \cot \left(\frac{\pi + (\phi-\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^+(\phi-\phi')] + \cot \left(\frac{\pi - (\phi-\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^-(\phi-\phi')] + \\ & R_{0 \perp} \cot \left(\frac{\pi - (\phi+\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^-(\phi+\phi')] + R_{n \perp} \cot \left(\frac{\pi + (\phi+\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^+(\phi+\phi')] \end{align} \right\rbrace [/math]

- [math] D_h = \frac{-e^{-j\pi/4}}{2n \sqrt{2\pi k} \sin\beta_0'} \left\lbrace \begin{align} & \cot \left(\frac{\pi + (\phi-\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^+(\phi-\phi')] + \cot \left(\frac{\pi - (\phi-\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^-(\phi-\phi')] + \\ & R_{0 \|} \cot \left(\frac{\pi - (\phi+\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^-(\phi+\phi')] + R_{n \|} \cot \left(\frac{\pi + (\phi+\phi')}{2n}\right) F[kLa^+(\phi+\phi')] \end{align} \right\rbrace [/math]

where F(x) is the Fresnel Transition function:

- [math] F(x) = 2j \sqrt{x} e^{jx} \int_{\sqrt{x}}^{\infty} e^{-j\tau^2} \, d\tau [/math]

In the above equations, we have

- [math] \begin{align} s = |\rho_D - \rho_S| \\ s' = |\rho_D - \rho_r| \end{align} [/math]

- [math]L = \frac{s s' \sin^2 \beta'}{s + s'} [/math]

- [math]a^{\pm}(\nu) = 2\cos^2 \left( \frac{2n\pi N^{\pm} - \nu}{2} \right), \quad \nu = \phi \pm \phi' [/math]

where [math]N^{\pm}[/math] are the integers which most closely satisfy the equations [math] 2n\pi N^{\pm} - \nu = \pm \pi [/math].

Multilayer Green’s Functions

The Green’s functions are the solutions of boundary value problems when they are excited by an elementary source. This is usually assumed to be an infinitesimally small vectorial point source. In order for Green’s functions to be computationally useful, they must have analytical closed forms like a mathematical expression, or one should be able to compute them using a recursive process. It turns out that only very few boundary value problems have closed-form Green’s functions. Planar layered structures with laterally infinite extents are one of those few cases, which can be represented by recursive dyadic Green's functions.

In general, a structure may support both electric (J) and magnetic (M) currents. The total electric (E) and magnetic (H) fields can be expressed in terms of the electric and magnetic currents in the following way:

- [math]E = E^{inc} + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') \cdot J(r') \, dv' + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{EM}(r|r') \cdot M(r') \, dv'[/math]

- [math]H = H^{inc} + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{HJ}(r|r') \cdot J(r') \, dv' + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{HM}(r|r') \cdot M(r') \, dv'[/math]

where GEJ, GEM, GHJ, GHM are the dyadic Green’s functions for the electric and magnetic currents due to electric and magnetic current source, respectively, and Ei and Hi are the incident or impressed electric and magnetic fields, respectively. In these equations, r is the position vector of the observation point and r' is the position vector of the source point. V is the volume that contains all the sources and the volume integration is performed with respect to the primed coordinates. The incident or impressed fields provide the excitation of the structure. They may come from an incident plane wave or a gap source on a microstrip line, a short dipole, etc. The complexity of the Green’s functions depends on what is considered as the background structure. If you remove all the unknown currents from the structure, you are left with the background structure.

Planar Integral Equations

To derive a system of integral equations, we enforce the boundary conditions on the integral definitions of the E and H fields as follows:

- [math]L_E(E) = L_E \bigg\{ E^{inc} + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') \cdot J(r') \, dv' + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{EM}(r|r') \cdot M(r') \, dv' \bigg\} [/math]

- [math]L_H(H) = L_H \bigg\{ H^{inc} + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{HJ}(r|r') \cdot J(r') \, dv' + \iiint\limits_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{HM}(r|r') \cdot M(r') \, dv' \bigg\} [/math]

where LE is the boundary value operator for the electric field and LH is the boundary value operator for the magnetic field. For example, LE may require that the tangential components of the Efield vanish on perfect conductors:

- [math] \hat{n} \times \hat{n} \times \mathbf{E} = 0, \quad \mathbf{r} \in PEC [/math]

Or LE and LH may require that the tangential components of the E and H fields be continuous across an aperture in a perfect ground plane:

- [math]\begin{cases} \hat{n} \times \hat{n} \times (\mathbf{E}^+ - \mathbf{E}^-) = 0 \\ \hat{n} \times \hat{n} \times (\mathbf{H}^+ - \mathbf{H}^-) = 0 \end{cases} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \mathbf{M}^+(r) = \mathbf{M}^-(r), \quad r \in PMC [/math]

Given the fact that the dyadic Green’s functions and the incident or impressed fields are all known, one can solve the above system of integral equations to find the unknown currents J and M.

In EM.Picasso, magnetic currents are always surface current with units of V/m. Electric currents, however, can be surface currents with units of A/m as in the case of metallic traces like microstrip lines, or they can be volume currents with units of A/m2 as in the case of perfectly conducting vias. Dielectric inserts are modeled as volume polarization currents that are related to the electric field E in the following manner:

- [math]\mathbf{J}_p(r) = jk_0 Y_0(\varepsilon_r - \varepsilon_b)\mathbf{E}(r)[/math]

where k0 is the free space propagation constant, [math]Y_0 = \tfrac{1}{Z_0} = \tfrac{1}{120\pi}[/math] is the free space intrinsic admittance, εr is the permittivity of the dielectric insert, and εb is the permittivity of its background layer. In a 2.5-D formulation, it is assumed that the volume currents have only a vertical component along the Z direction, and their circumferential components are negligible.

Numerical Solution of Integral Equations

The planar integral equations derived earlier can be solved numerically by discretizing the unknown currents using a proper meshing scheme. The original functional equations are reduced to discretized linear algebraic equations over elementary cells. The unknown quantities are found by solving this system of linear equations, and many other parameters can be computed thereafter. This method of numerical solution of integral equations is known as the Method of Moments (MoM). In this method, the unknown electric and magnetic currents are represented by expansions of basis functions as follows:

- [math]J(r) = \sum_{n=1}^N I_n^{(J)} f_n^{(J)} (r)[/math]

- [math]M(r) = \sum_{k=1}^K V_k^{(M)} f_k^{(M)} (r)[/math]

where [math]f_n^{(J)}[/math] and [math]f_k^{(M)}[/math] are the generalized vector basis functions for the expansion of electric and magnetic currents, respectively, and [math]I_n^{(J)}[/math] and [math]V_k^{(M)}[/math] are the unknown amplitudes of these basis functions, which have to be determined. Substituting these expansions into the integral equations generates a set of discretized integral equations, which can further be converted to a system of linear algebraic equations. This is accomplished by testing the discretized integral equations using the a set of test functions. In the method of moments, the Galerkin technique is typically used, which chooses the expansion basis functions as test functions. This leads to the following linear system:

- [math] \begin{bmatrix} Z^{(EJ)} & T^{(EM)} \\ U^{(HJ)} & Y^{(HM)} \end{bmatrix} \cdot \begin{bmatrix} I^{(J)} \\ V^{(M)} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} V^{(E)} \\ I^{(M)} \end{bmatrix} [/math]

where

- [math] Z_{ij}^{(EJ)} = \iiint\limits_{V_i} dv f_i^{(J)}(r) \cdot \iiint\limits_{V_j} dv' \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') \cdot f_i^{(J)}(r')[/math]

and

- [math] V_i^{(E)} = \iiint\limits_{V_i} dv f_i^{(J)}(r) \cdot E^{inc}(r) [/math]

- [math] I_i^{(H)} = \iiint\limits_{V_i} dv f_i^{(M)}(r) \cdot H^{inc}(r) [/math]

Similar expressions can be derived for the T(EM), U(HJ) and Y(HM)elements of the MoM matrix.

Discretization Of Electric & Magnetic Currents

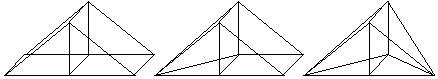

The right choice of the basis functions to represent the elementary currents is very important. It will determine the accuracy and computational efficiency of the resulting numerical solution. Rooftop basis functions are one of the most popular types of basis functions used in a variety of MoM formulations. The surface currents (whether electric or magnetic) are discretized using 2D rooftop basis functions shown in the figure below:

Rooftop or RWG basis functions built over two rectangular, triangular or mixed cells.

The rooftop basis functions are defined over two adjacent cells with a common edge of length. If the two cells are triangular, then the so-called RWG functions are obtained. It is also possible to define rooftop functions over two adjacent rectangular cells or two adjacent rectangular and triangular cells with a common edge. On a rectangular cell, the function is defined as having a (descending or ascending) linear profile in one direction and a constant profile in the other perpendicular direction.

The volume polarization currents in 2.5-D MoM have a vertical direction along the Z-axis. These are discretized using prismatic basis functions that have either a rectangular or triangular base with a constant profile along the Z-axis.

Prismatic basis functions built over single triangular and rectangular cells.

The Rectangular Mesh Advantage

Rectangular cells offer a major advantage over triangular cells for numerical MoM simulation of planar structures. This is due to the fact that the dyadic Green's functions of planar layered background structures are space-invariant on the transverse plane. Recall that the elements of the moment matrix are given by the following equation:

- [math] Z_{ij}^{(\mu \nu)} = \iiint_{V_i} d\nu f_i^{(\mu)}(r) \cdot \iiint_{V_j}d\nu ' \overline{\overline{G}}_{\mu \nu}(r|r') \cdot f_j^{(v)}(r') [/math]

where the spatial-domain dyadic Green's functions are a function of the observation and source coordinates, rand r' . The MoM matrix elements can indeed be interpreted as interactions between two elementary basis functions fi(r) and fj(r') on that particular background structure. The spatial-domain dyadic Green's functions can themselves be expressed in terms of the spectral-domain dyadic Green's functions as follows:

- [math] \overline{\overline{G}}_{\mu \nu}(r|r') = \frac{1}{(2\pi)^2} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{\mu \nu} (k_p, z|z') e^{-j[k_x(x-x')+k_y(y-y')]} \, dk_x \, dk_y , \quad {k_p}^2 = {k_x}^2 + {k_y}^2 [/math]

where the doubly infinite integration is performed with respect to the spectral variables kx and ky. As can be seen from the above expression, the spatial-domain dyadic Green's functions are functions of z, z', as well as (x-x') and (y-y'). The MoM matrix elements can now be transformed into the spectral domain as

- [math] Z_{ij}^{(\mu \nu)} = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^2} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \tilde{f}_i^{(\mu)} (k_x, k_y) \cdot \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{\mu \nu} (k_{\rho}, z|z') \cdot \tilde{f}_j^{(\nu)} (k_x, k_y) \, dk_x \, dk_y [/math]

where the tilde symbol signifies the Fourier transform of a function defined as

- [math] \tilde{f}(k_x, k_y) = \dfrac{1}{(2\pi)^2} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} f(x,y) e^{j(k_x x + k_y y)} \, dx \, dy [/math]

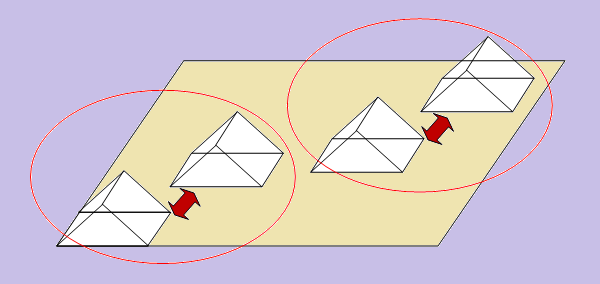

Rectangular cells have simple Fourier transforms. The rooftop basis functions are triangular functions in the direction of current flow and constant in the perpendicular direction. This means that their Fourier transform is a product of a sinc-squared function along one spectral direction and a sinc function along the other. You can see from the figure below that if one deals with a rectangular mesh of identical cells (all equal and parallel), then the interactions among the rooftop basis functions become a functions of the index differences and not the absolute indices:

- [math] Z_{(i,k)|(j,l)} = Z \Big\langle f_{i,k}(x,y)| f_{j,l}(x', y') \Big\rangle = Z_{(i-j)|(k-l)} [/math]

In the above equation, the vectorial rooftop basis functions have explicit, double indices: i and k along the local X and Y directions, respectively, for the test (observation) basis function, and j and l along the local X and Y directions, respectively, for the expansion (source) basis function. Thus, uniform rectangular cells, i.e. structured rectangular cells of identical size aligned in the same direction, can speed up the planar MoM simulation significantly due to these symmetry and the invariance properties. For example, all the self-interactions are identical regardless of the location of a rooftop basis function. This reduces the matrix fill process for a total of N rooftop basis functions from an N2 process to one of order N.

Pairs of rooftop basis functions that have identical MoM interactions.

Computing The Near Fields in Planar MoM

Once all the current distributions are known in a planar structure, the electric and magnetic fields can be calculated everywhere in that structure using the dyadic Greens's functions of the background structure:

- [math] \begin{align} \mathbf{E(r) = E_{inc}(r)} + & \sum_{n=1}^N I_n^{(J)} \iiint_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') \cdot f_n^{(J)}(r') \, d\nu' + \\ & \sum_{k=1}^K V_n^{(M)} \iiint_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{EM}(r|r') \cdot f_k^{(M)}(r') \, d\nu' \end{align} [/math]

- [math] \begin{align} \mathbf{H(r) = H_{inc}(r)} + & \sum_{n=1}^N I_n^{(J)} \iiint_V \overline{\overline{G}}_{HJ}(r|r') \cdot f_n^{(J)}(r') \, d\nu' + \\ & \sum_{k=1}^K V_n^{(M)} \iiint_V \overline{\overline{G}} {HM}(r|r') \cdot f_k^{(M)}(r') \, d\nu' \end{align} [/math]

The above equations can be cast into the spectral domain as follows:

- [math] \begin{align} \mathbf{E(r) = E_{inc}(r)} + \frac{1}{(2\pi)^2} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \bigg[ & \sum_{n=1}^N I_n^{(J)} \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{EJ}(k_{\rho}, z|z') \cdot \tilde{f}_n^{(J)}(k_x, k_y) + \\ & \sum_{k=1}^K V_n^{(M)} \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{EM}(k_{\rho}, z|z') \cdot \tilde{f}_k^{(M)}(k_x, k_y) \bigg] \, dk_x \, dk_y \end{align} [/math]

- [math] \begin{align} \mathbf{H(r) = H_{inc}(r)} + \frac{1}{(2\pi)^2} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int\limits_{-\infty}^{\infty} \bigg[ & \sum_{n=1}^N I_n^{(J)} \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{HJ}(k_{\rho}, z|z') \cdot \tilde{f}_n^{(J)}(k_x, k_y) + \\ & \sum_{k=1}^K V_n^{(M)} \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{HM}(k_{\rho}, z|z') \cdot \tilde{f}_k^{(M)}(k_x, k_y) \bigg] \, dk_x \, dk_y \end{align} [/math]

Calculation of the near-zone fields (fields at the vicinity of the unknown currents) is done at the post-processing stage and in a Cartesian coordinate systems. These calculations involve doubly infinite spectral-domain integrals, which are computed numerically. As was mentioned earlier, EM.Cube's planar MoM engine rather uses a polar integration scheme, where the radial spectral variable kρ is integrated over the interval [0, Mk0], M being a large enough number to represent infinity, and the angular spectral variable t is integrated over the interval [0, 2π]. You also saw some of the numerical parameters related to this spectral-domain integration scheme.

Computing The Far Fields in Planar MoM

Unlike differential-based methods, MoM simulators do not need a radiation box to calculate the far field data. The far-zone fields are calculated directly by integrating the currents on the traces and across the embedded objects using the asymptotic form of the background structure’s dyadic Green's functions:

- [math] \mathbf{E^{ff}(r)} = \iiint_V \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ,ff}(r|r') \cdot J(r') } \, d\nu ' + \iiint_V \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{EM,ff}(r|r') \cdot M(r') } \, d\nu '[/math]

- [math] \mathbf{H^{ff}(r)} = \dfrac{1}{\eta_0} \mathbf{ \hat{r} \times E^{ff}(r) }[/math]

where η0 = 120π is the characteristic impedance of the free space. As can be seen from the above equations, the far fields have the form of a TEM wave propagating in the radial direction away from the origin of coordinates. This means that the far-field magnetic field is always perpendicular to the electric field and the propagation vector, which in this case happens to be the radial unit vector in the spherical coordinate system. In other words, one only needs to know the far-zone electric field and can easily calculate the far-zone magnetic field from it. In EM.Cube's mixed potential integral equation formulation, the far-zone electric field can be expressed in terms of the asymptotic form of the vector electric and magnetic potentials A and F:

- [math]\mathbf{E^{ff}}(x,y,z) = j k_0 \eta_0 \hat{r} \times [\hat{r} \times \mathbf{A}(r \to \infty)] + j k_0 \hat{r} \times \mathbf{F}(r \to \infty)[/math]

The asymptotic form of these vector potentials are calculated using the "Method of Stationary Phase" when k0r → ∞. In that case, one can use the approximation:

- [math] k_0 |\mathbf{r-r'}| \approx k_0 (r - \mathbf{\hat{r} \cdot r'}) [/math]

After applying the stationary phase method, one can extract the spherical wave factor exp(-jk0r)/r from the far-zone electric field, leaving the rest as functions of the spherical angles θ and φ. In other words, the far field is normalized to r, the distance from the field observation point to the origin. It is customary to express the far fields in spherical components Eθ and Eφ. Note that the outward propagating, TEM-type, far fields do not have radial components, i.e. Er = 0.

- [math] \mathbf{E_{\theta}}(\theta, \phi) = \cos\theta \cos\phi E_x + \cos\theta \sin\phi E_y - \sin\theta E_z [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{E_{\phi}}(\theta, \phi) = -\sin\phi E_x + \cos\phi E_y [/math]

Periodic Planar MoM Simulation

In the case of an infinite periodic planar structure, the field equations can be written in the following form:

- [math] \mathbf{E(r) = E^{inc}(r)} + \sum_{m=-\infty}^{\infty} \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \bigg[ \iiint_V \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{EJ}(r|r') \cdot J_{mn}(r') } \, d\nu' + \iiint_V \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{EM}(r|r') \cdot M_{mn}(r') } \, d\nu' \bigg] [/math]

- [math] \mathbf{H(r) = H^{inc}(r)} + \sum_{m=-\infty}^{\infty} \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \bigg[ \iiint_V \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{HJ}(r|r') \cdot J_{mn}(r') } \, d\nu' + \iiint_V \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{HM}(r|r') \cdot M_{mn}(r') } \, d\nu' \bigg] [/math]

where

- [math]\mathbf{J_{mn}(r) = J_{mn}}(x,y,z) = \mathbf{J_{00}}(x+m S_x, y+n S_y, z) e^{j(m k_{x00} S_x + n k_{y00} S_y)}[/math]

- [math]\mathbf{M_{mn}(r) = M_{mn}}(x,y,z) = \mathbf{M_{00}}(x+m S_x, y+n S_y, z) e^{j(m k_{x00} S_x + n k_{y00} S_y)}[/math]

and

- [math] -\infty \lt m, n \lt \infty [/math]

In the above equations, [math]\mathbf{J_{00}(r)}[/math] and [math]\mathbf{M_{00}(r)}[/math] are the periodic unit cell's electric and magnetic currents that are repeated everywhere in space on a rectangular lattice with periods Sx and Sy along the X and Y directions, respectively. [math]k_{x00}[/math] and [math]k_{y00}[/math] are the periodic propagation constants along the X and Y directions, respectively, and they are given by:

- [math] k_{x00} = k_0 \sin\theta \cos\phi [/math]

- [math] k_{y00} = k_0 \sin\theta \sin\phi [/math]

where θ and φ are the beam scan angles in the case of periodic excitation of lumped sources, or they are the spherical angles of incidence in the case of a plane wave source illuminating the periodic structure. Using the infinite summations, one can define periodic dyadic Green's functions in the spectral domain in the following manner:

- [math] \mathbf{ \overline{\overline{G}}_{\mu \nu}^{PER} (r|r') } = \frac{1}{S_x S_y} \sum_{m=-\infty}^{\infty} \sum_{n=-\infty}^{\infty} \mathbf{ \tilde{\overline{\overline{G}}}_{\mu \nu} } (k_x, k_y, z|z') e^{-j[k_{xm}(x-x') + k_{yn}(y-y')]} [/math]

where

- [math] k_{xm} = k_{x00} + \frac{2\pi m}{S_x} \quad \text{and} \quad k_{ym} = k_{y00} + \frac{2\pi m}{S_y} [/math]

The above doubly infinite periodic Green's functions are said to be expressed in terms of "Floquet Modes". The exact formulation involves an infinite set of these periodic Floquet modes. During the MoM matrix fill process for a periodic structure, a finite number of Floquet modes are calculated. By default, EM.Cube's planar MoM engine considers Mx = My = 25. This implies a total of 51 modes along the X direction and a total of 51 modes along the Y direction, or a grand total of 512 = 2,601 Floquet modes. You can increase the number of Floquet modes for your project from the Planar MoM Engine Settings Dialog. In the section titled "Periodic Simulation", you can change the values of Number of Floquet Modes in the two boxes designated X and Y.

EM.Picasso's Linear System Solvers

After the MoM impedance matrix [Z] (not to be confused with the impedance parameters) and excitation vector [V] have been computed through the matrix fill process, the planar MoM simulation engine is ready to solve the system of linear equations:

- [math] \mathbf{[Z]}_{N\times N} \cdot \mathbf{[I]}_{N\times 1} = \mathbf{[V]}_{N\times 1} [/math]

where [I] is the solution vector, which contains the unknown amplitudes of all the basis functions that represent the unknown electric and magnetic currents of finite extents in your planar structure. In the above equation, N is the dimension of the linear system and equal to the total number of basis functions in the planar mesh. EM.Cube's linear solvers compute the solution vector[I] of the above system. You can instruct EM.Cube to write the MoM matrix and excitation and solution vectors into output data files for your examination. To do so, check the box labeled "Output MoM Matrix and Vectors" in the Matrix Fill section of the Planar MoM Engine Settings dialog. These are written into three files called mom.dat1, exc.dat1 and soln.dat1, respectively.

There are a large number of numerical methods for solving systems of linear equations. These methods are generally divided into two groups: direct solvers and iterative solvers. Iterative solvers are usually based on matrix-vector multiplications. Direct solvers typically work faster for matrices of smal to medium size (N<3,000). EM.Cube's Planar Module offers five linear solvers:

- LU Decomposition Method

- Biconjugate Gradient Method (BiCG)

- Preconditioned Stabilized Biconjugate Gradient Method (BCG-STAB)

- Generalized Minimal Residual Method (GMRES)

- Transpose-Free Quasi-Minimum Residual Method (TFQMR)

Of the above list, LU is a direct solver, while the rest are iterative solvers. BiCG is a relatively fast iterative solver, but it works only for symmetric matrices. You cannot use BiCG for periodic structures or planar structures that contain both metal and slot traces at different planes, as their MoM matrices are not symmetric. The three solvers BCG-STAB, GMRES and TtFQMR work well for both symmetric and asymmetric matrices and they also belong to a class of solvers called Krylov Sub-space Methods. In particular, the GMRES method always provides guaranteed unconditional convergence.